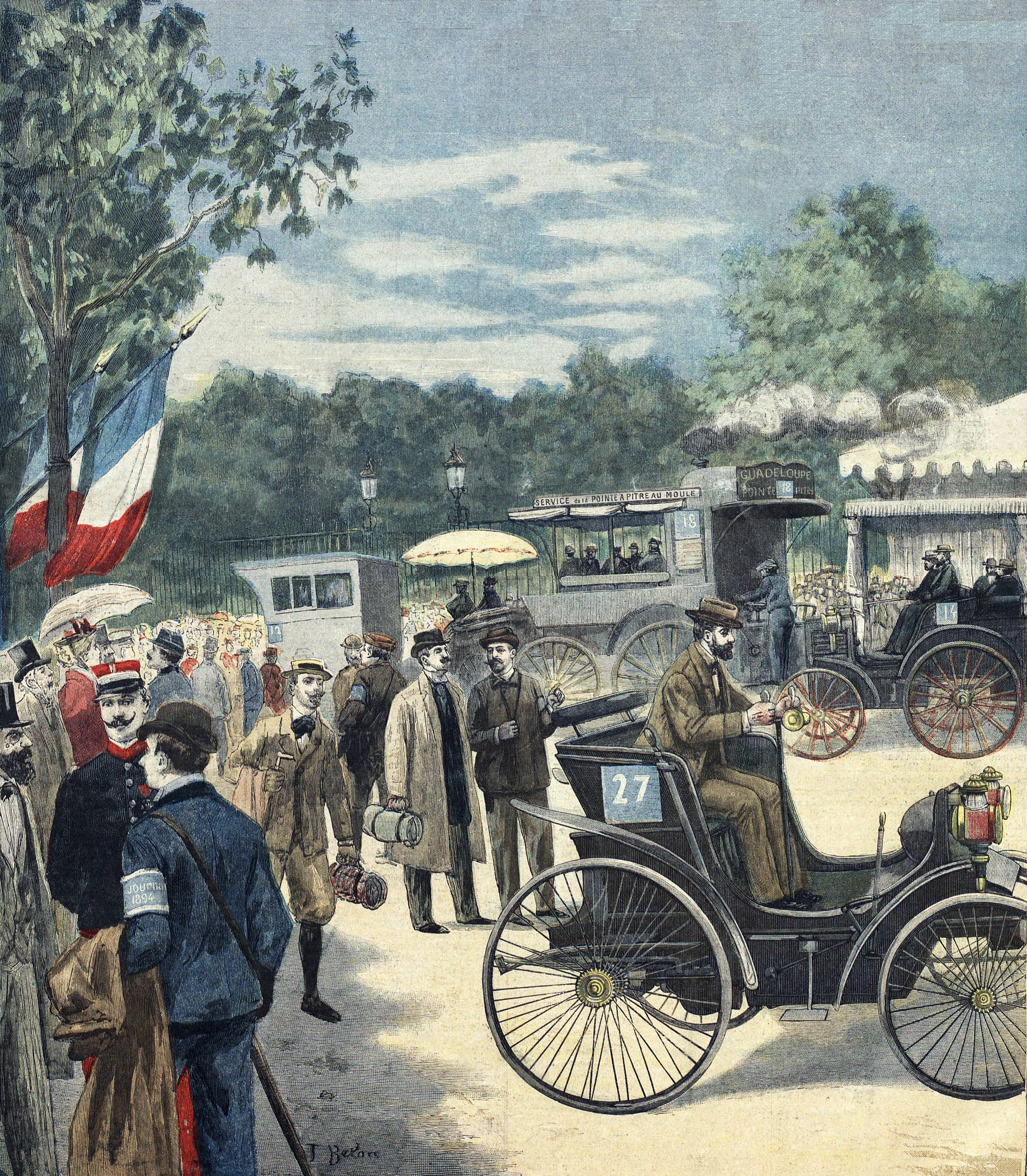

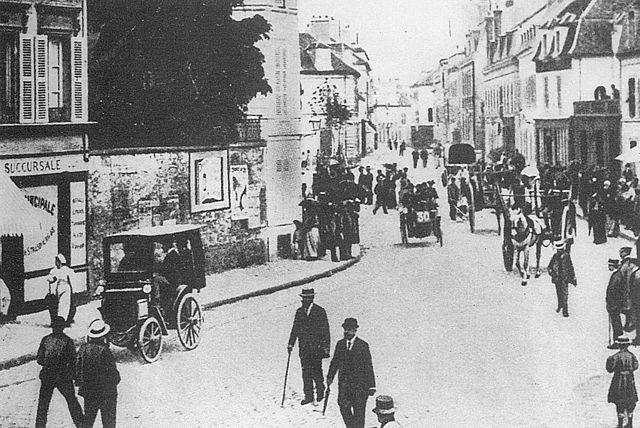

Paris-Rouen - the first automobile competition in the World (“Le Petit Journal”, 1894)

James Laux (In the first gear, 1976) wrote, "Pierre Giffard (1853–1922) was a French journalist, the editor of “Le Petit Journal”. James Locks wrote, “In promoting automobiles the journalists played an essential role. The publicity they gave to the new machines speeded the industry's growth immeasurably. Pierre Giffard led the way. Writing for the very widely circulated Le Petit journal, he had promoted the Paris-Brest-Paris bicycle race in 1891, a great success. Now he attempted something similar for automobiles, and announced a competition for horseless vehicles in the summer of 1894 (July 19-22). This time he did not organize a race but simply a promenade or road test from Paris to Rouen, a distance of 125 km.”

“Le Petit Journal” offered 10000 francs of prizes. Giffard’s criteria were safety, simplicity and economy of operation. The speed was not a main criterion, so this competition could not be considered a race in the conventional sense of the term.

Emile Levassor wrote to Daimler, "The contest of the "Petit Journal" is postponed to July 1894. Many manufacturers apparently claimed they were not ready. As for us we protested. You know what this contest consists of; I will repeat it briefly:

- An elimination round of about 50 km on one of the 6 routes. The distance will have to be traveled at an average speed of 12 ½ km/h. That is to say 50 km in four hours.

- Cars which have passed the above test will be permitted to take part in the final round from Paris to Rouen, approximately 129 km.

It is certain that many cars (there are 102 registered) will be eliminated during the first event, the 6 routes being for some difficult. There are two in particular, which are very bad: that of Paris to Rambouillet which traverses a very rugged country and partly paved roads with long, and that of Paris to Magny which is paved for more than 35 km. In my opinion the cars that will have the misfortune to end up on these two courses, if they make it in 4 hours, will be good and solid cars. The other four courses are easier. As for the road from Paris to Rouen, it is quite good, though hilly in a certain part. The question of speed will come into play, but in a relative way only, one will also look for the ease of driving, comfort, solidity, safety, cleanliness etc. etc. Regarding the "Petit Journal" competition, I believe that the obligation to submit each car to the Engineers of the Prefecture of Police to find out if they are able to drive without accident significantly reduces the number of vehicles.”

One hundred and two vehicles were originally registered but when the moment of truth arrived late in July only twenty-one appeared on the starting line. Fourteen of these used petrol engines, all on the Daimler design and built by Panhard & Levassor except for one Roger-Benz. The other seven were steamers.

The groups that set off from Porte Maillot on Thursday 19 July were:

- Itinerary one – Paris to Mantes-la-Jolie via Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye and Flins-sur-Seine:

- No. 3 de Dion, Bouton et Cie, break, six seats, steam. – Did not qualify for Paris-Rouen.

- No. 13 Panhard et Levassor, four seats, petrol – qualified

- No. 21 Letar, four seats, steam – did not qualify

- No. 30 Les fils de Peugeot frères, three seats, petrol – qualified

- Itinerary two – Paris to Mantes-la-Jolie via Poissy and Triel-sur-Seine:

- No. 10 Scotte, 8–10 seats, steam – qualified

- No. 15 Panhard et Levassor, two seats, petrol – qualified

- No. 25 Coqatrix, four seats, steam – qualified

- No. 28 Les fils de Peugeot frères, four seats, petrol – qualified

- No. 44 de Prandieres, six seats, system Serpollet and petrol combined– qualified

- Itinerary four – Paris to Rambouillet via Versailles and Dampierre-en-Yvelines:

- No. 7 Gautier, four seats, steam – qualified

- No. 18 Archdeacon, six or seven seats, steam – qualified

- No. 19 Le Blant, eight to ten seats, steam – qualified

- No. 42 Le Brun, four seats, petrol – qualified

- Itinerary five – Paris to Corbeil-Essonnes via Versailles and Palaiseau:

- No. 4 de Dion, Victoria, four people, steam – qualified

- No. 16 Quantin, six seats, petrol – did not qualify

- No. 27 Les fils de Peugeot frères, two seats, petrol – qualified

- No. 29 Les fils de Peugeot frères, four seats, petrol – did not qualify

- No. 40 Lemoigne, four seats, 'gravity powered'. Note – did not show or was eliminated.

- Itinerary six – Paris to Précy-sur-Oise via Gennevilliers and L'Isle-Adam, Val-d'Oise:

- No. 12 Tenting, four seats, petrol. Note – did not qualify for Paris-Rouen.

- No. 14 Panhard et Levassor, four seats, (new type) petrol – qualified

- No. 24 Alfred Vacheron, two seats, petrol – did not qualify until Saturday 21st

- No. 31 Les fils de Peugeot frères, break, five seats, petrol – qualified

On Friday 20 July a second qualifying event was run over two routes.

Itinerary one – Paris to Mantes-la-Jolie via Bezons, Houilles and Maisons-Laffitte.

-

- No. 44 de Prandieres, six seats, system Serpollet and petrol combined – qualified

- No. 60 Le Blant, Serpollet, nine seats, steam – qualified

- No. 64 Émile Mayade, Panhard et Levassor, four seats, petrol – qualified

- No. 65 Albert Lemaître, Les fils de Peugeot frères, four seats, petrol – qualified

- Itinerary two – Paris to Corbeil-Essonnes

- No. 61 Roger de Montais, De Montais, two seat tricycle, petrol – qualified

- No. 85 Émile Roger, Benz, two seats, petrol – qualified

On Saturday 21 July a third qualifying event was run from Paris to Poissy.

-

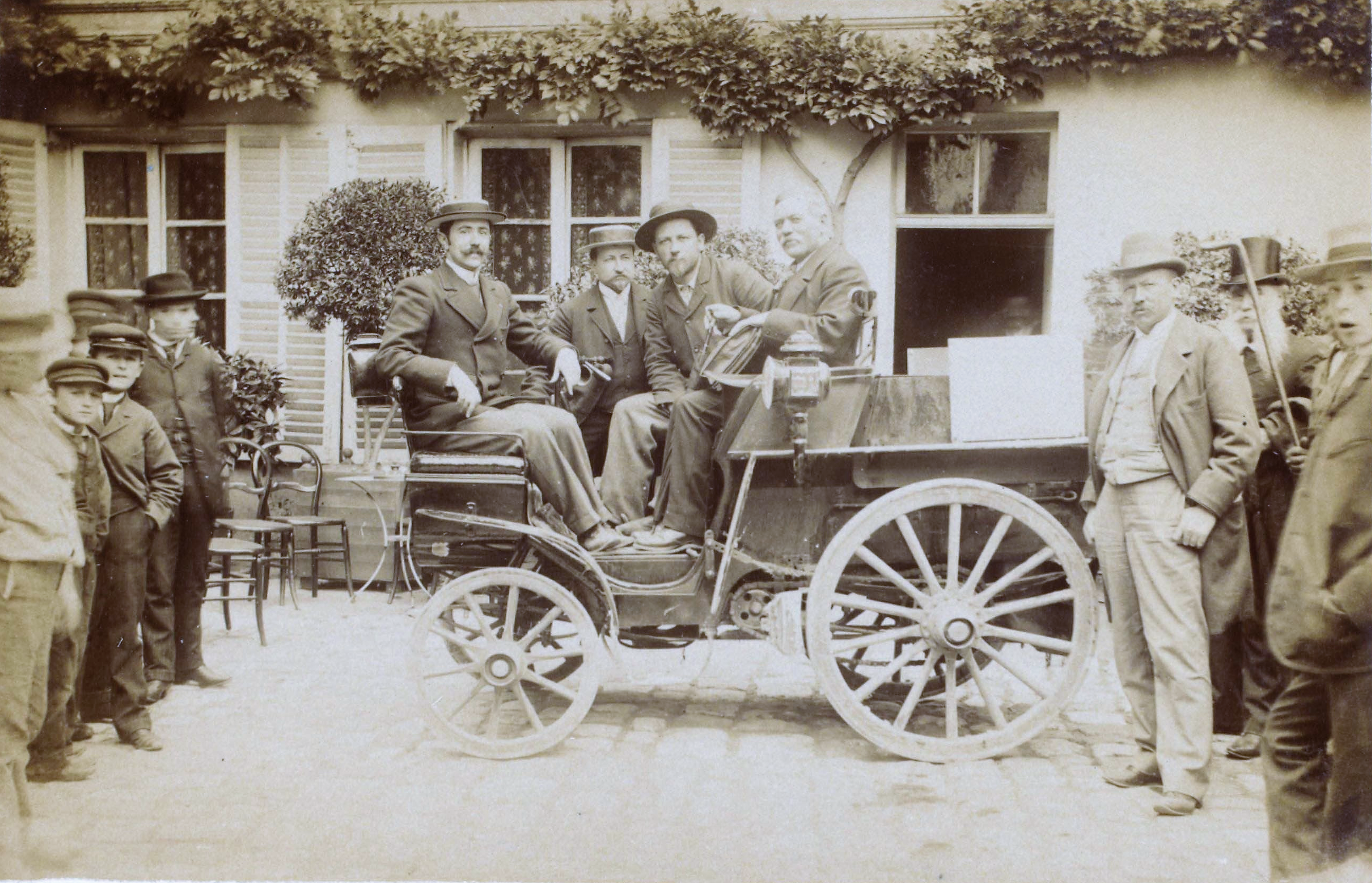

- No. 53 de Bourmont (de Bourmont, four seats, petrol) – qualified

- No. 24 Alfred Vacheron, two seats, petrol – qualified

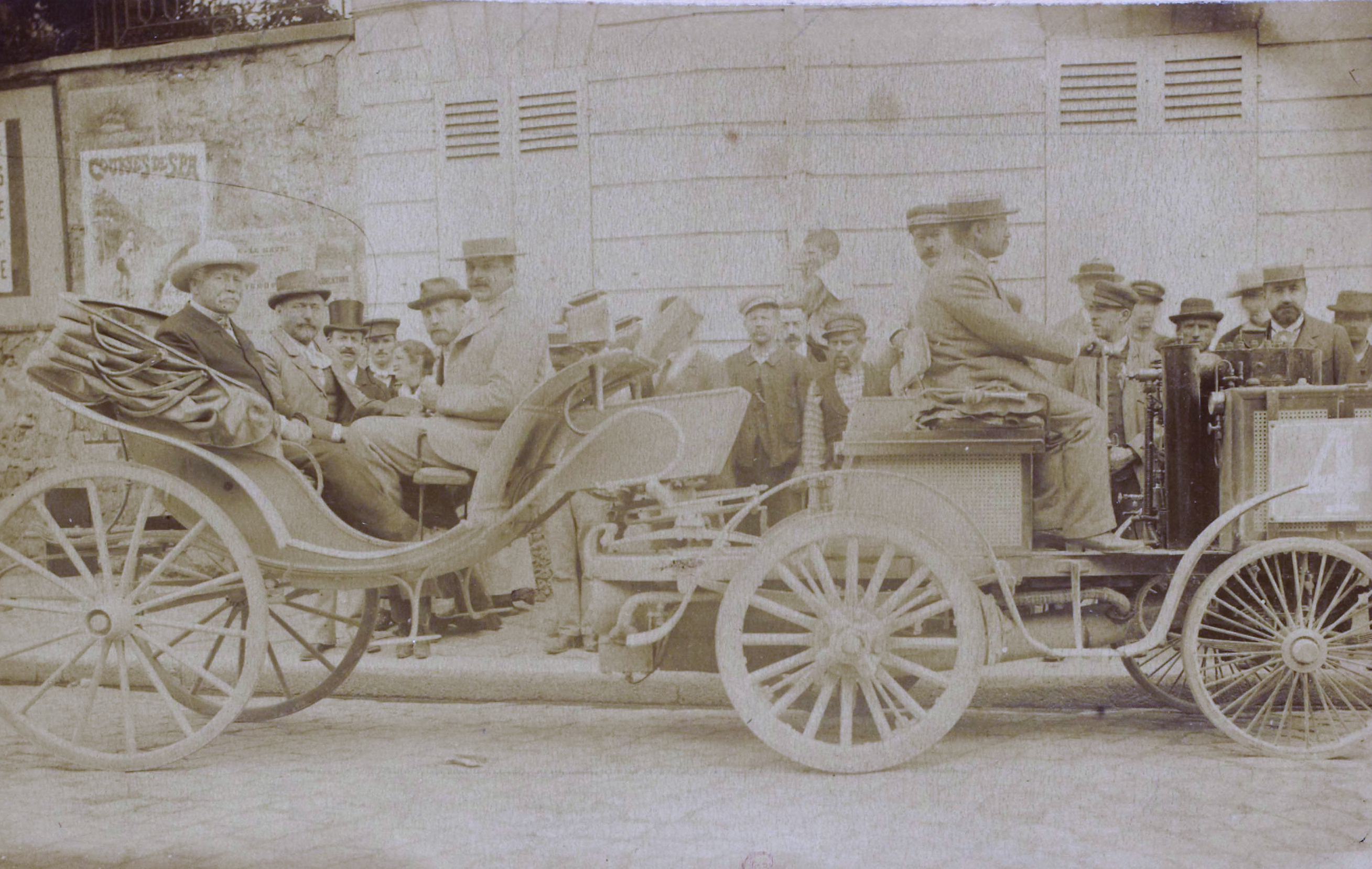

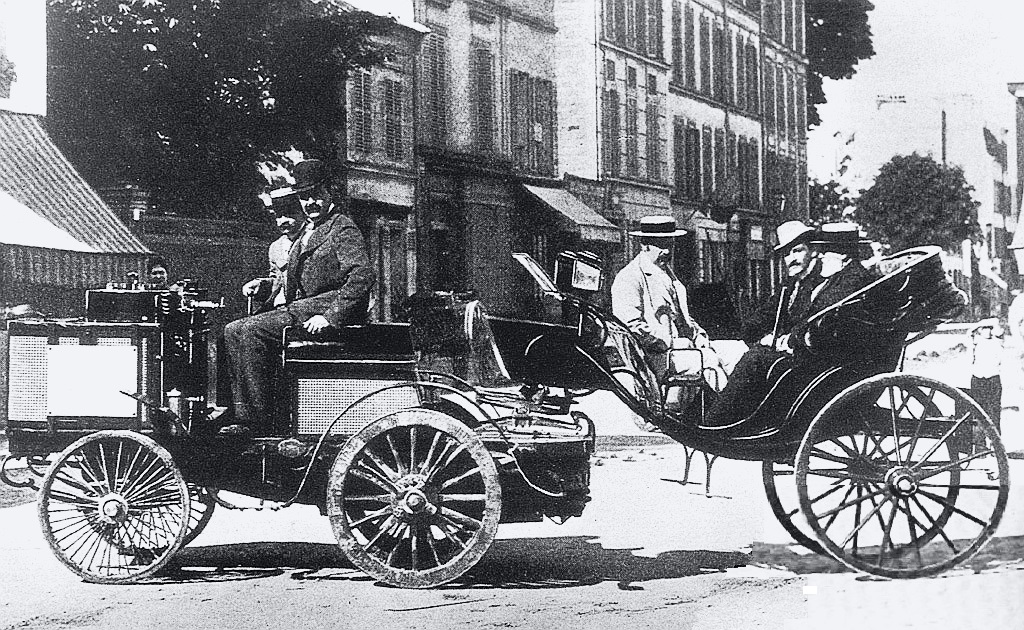

Original photographs by R.Girard:

M. de Bourmont

“The Hub” wrote in 1894, "…For some days previous to the trials, horseless carriages were to be met in the streets of Paris and neighborhood, exercising for the approaching contest. Though one hundred and two carriages were entered for competition, to be impelled by various motors, fifty-six failed to put in an appearance at the roll-call.

Even then, somewhere, by some mishaps, prevented from taking part in the contest, so that the task of weeding out faulty of unsuitable vehicles was rendered easier for the judges than it would have been had all remained.

The twenty-one carriages went off in very fine weather, escorted by about 500 cyclists, ten per cent being lady riders in knickerbockers and short skirts, on safeties. The pace of the horseless carriages at some parts of the journey was 15 miles an hour. The hills were readily mounted, but newly laid road material stopped two for a time.

One had a tube burst, which delayed it; one's supply of petroleum ran short. The results of the journey are shown of seventeen vehicles that accomplished it but it may be stated that fast speed or high finish would not count with the judges as points of merit; this was to give poor inventors a chance with their vehicles in the contest”

On July 27, 1894, “The Engineer” published the story from one of the special commissioners who was not only witness of Paris-Rouen competition but took part as passenger on different types of cars:

“The Daimler motor was very well represented by the two firms Panhard & Levassor and Les Fils de Peugeot Frères. My first impression as to the entire absence of smell of this motor when working has become considerably modified. The fact is, that in such a building as that used for testing the motor to which I previously referred, the air is still and the products of combustion, rising in a vertical pipe which terminates above the head of a person, escape upwards, but when the motor is placed in a carriage the smell of the exhaust is noticeable, and although while the vehicle is travelling it may not be noticed for long periods, still in mountain incline it becomes at times very unpleasant, and this will occur more particularly if the lubrication of the motor is not carefully attended to. The most serious objection to the carriages fitted with these motors is the great vibration which takes place while the carriage is at rest. If the carriage is fully loaded the movement is not so noticeable, as the bearing springs are of course compressed, but if it is empty the vibration is excessive.

The application of the motor to the carriage is practically the same by the two firms, Panhard & Levassor and Les Fils de Peugeot Freres, except that the former usually seem to prefer to place the motor in front of the vehicle, while the latter put it behind.

In my opinion the rear position is decidedly the better, as the smell is more readily carried away from the passengers by the wind when the carriage is moving. But it is somewhat difficult with some types of carriage to obtain a proper balance of the parts, and this leads to slight differences in design.

On Sunday (July 22) morning, at 7AM, I presented myself at the Porte Maillot, and at 7.45AM. I found that the whole of the twenty-one vehicles still in the competition had arrived. M. Giffard and his assistants very kindly set themselves to work again to find places for the engineers who were acting in a consultative capacity, and by 8AM every one was seated. The trembling of the carriages fitted with petroleum motors ceased, and the procession proceeded between rows of people down the Avenue de Neuilly. By the invitation of M. Giffard, whose “nom-de-plume” is “Jean-sans-terre", I took my seat in N13, a carriage for four persons, two being seated looking forward, and the other two with their backs to the former. The vehicle was built by Messrs. Panhard & Levassor and Mr. Panhard, junior (Hippolyte Panhard’s car), was driving. In travelling along the road in a carriage going somewhat more rapidly than several of the others, I had a good opportunity of noting the movements of the springs and of the guiding apparatus. That of Messrs. Peugeot appeared to work exceedingly well, and while allowing a very easy motion did not seem to be affected by the passage of the wheels over small stones. Both Messrs. Panhard & Levassor, and Messrs. Peugeot use a radial lever for steering, and it seems to act perfectly for these light carriages.

My own opinion is that steam is quite unsuitable for private persons who wish to drive their own carriages. The objections to the use of petroleum, or rather gasoline, are, first, the smell, which, when the motor is running properly, is almost absent; and, secondly, the vibration while at rest. I was anxious to see the electric motor which was entered, but it did not appear.”

Count de Dion was the first to arrive in Rouen after 6 hours 48 minutes at an average speed of 19 km/h (12 mph). He finished 3 min 30 sec ahead of Albert Lemaître (Peugeot), Auguste Doriot (Peugeot) (16 min 30 sec back), Hippolyte Panhard (Panhard) (33 min 30 sec) and Émile Levassor (Panhard) (55 min 30 sec). The winner's average speed was 17 km/h (11 mph).

The following first-hand account of the trial will be of interest:

"Everyone who took part in this journey will have a memory which will last them all through their lives. At the windows and doors old people saluted with emotion these vehicles of the future, of the very near future. School-masters and nuns brought their pupils out to be present at a spectacle which will be remembered in the annals of the country. On arriving at the Pont-de-l'Arche, we (in the De Dion car) were thrown against a balustrade of some hundreds of yards' length. With wonderful alertness, the 'Capitaine de Place' and Le Comte De Dion called some peasants to their aid, and the vehicle was righted. Later on, a fresh danger arose. We took the wrong road, through a false guide post, and, the driver making a wrong turn, we were landed in a potato field. Again, the vehicle was rescued by the energy of the 'Capitaine de Place, and we reached Rouen at 5.30, where we were greeted by the crowd with prolonged cheers, as were likewise the succeeding carriages. " (Claude Johnson, "The early history of motoring")

On Tuesday 24 July Le Petit Journal announced the prizes :

- First prize, the Prix du Petit Journal for "the competitor whose car comes closest to the ideal" (5,000 francs) was shared equally between Panhard et Levassor and 'Les fils de Peugeot Frères'.

- Second prize, the Prix Marinoni (2,000 francs) was awarded to de Dion, Bouton et Cie for their "interesting steam tractor that works like a horse and gives both absolute speed and pulling power up hills".

- Third prize, the Prix Marinoni (1,500 francs) was awarded to Maurice Le Blant for his nine-seater vehicle powered by the 'systeme Serpollet'.

- Fourth prize, the Prix Marinoni (1,000 francs) was shared between two manufacturers, Alfred Vacheron (No. 24) and Le Brun (No. 42).

- Fifth prize, the Prix Marinoni (500 francs) was awarded to Roger (No. 85)

Hello dear motorist friends,

This article is of great interest with all these extraordinary pictures which bring back a living past so accurately.

I have been studying this history for some time, starting in the middle of 19th century and ending in the 1980es.

Concretely it is presented by 125 dioramas with 665 models in 1/43 size. They have been on exhibition lately for 18 months at the CITE DE L’AUTOMOBILE – COLLECTION SCHUMPF in Mulhouse-France.

A book is published next month, I think you may be interested, although for the moment in french. But the english text is ready. I will send you separately an offer from the editor, you may have a look at the book and take contact with him.

I enjoyed your post on the Paris-Rouen “Race” tremendously. It actually helped fill in some gaps about which cars were in the Race. The extra history you supplied was a bonus! Thanks for putting this together and posting it.