England is the true home of the motor vehicle.

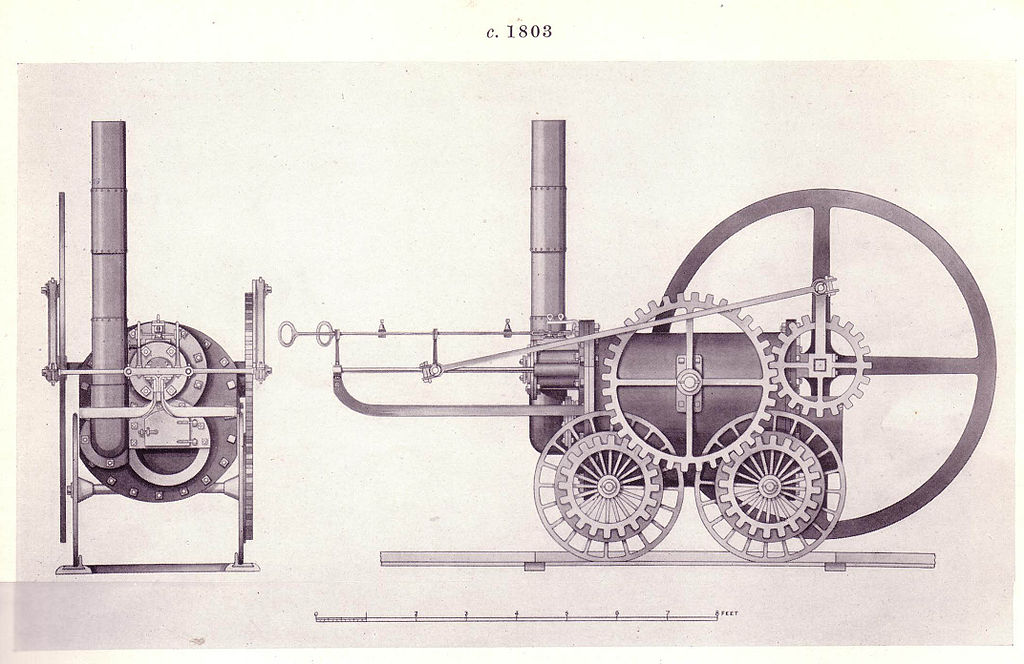

In 1802, Trevithick took out a patent for his high-pressure steam engine. To prove his ideas, he built a stationary engine at the Coalbrookdale Company's works in Shropshire in 1802, and Coalbrookdale company built a rail locomotive for him.

A drawing of the Coalbrookdale locomotive from the Science Museum

In 1813, William Hedley and Timothy Hackworth designed a locomotive (Puffing Billy). It was the first commercial adhesion steam locomotive, employed to haul coal chaldron wagons from the mine at Wylam to the docks at Lemington-on-Tyne in Northumberland.

The first railroad built in Great Britain to use steam locomotives was the Stockton and Darlington, opened in 1825. It used a steam locomotive built by George Stephenson and was practical only for hauling minerals.

The first modern railroad (Liverpool and Manchester Railway) was opened in 1830.

In the mid-19th century, England was the most advanced country in the field of motorization of transport.

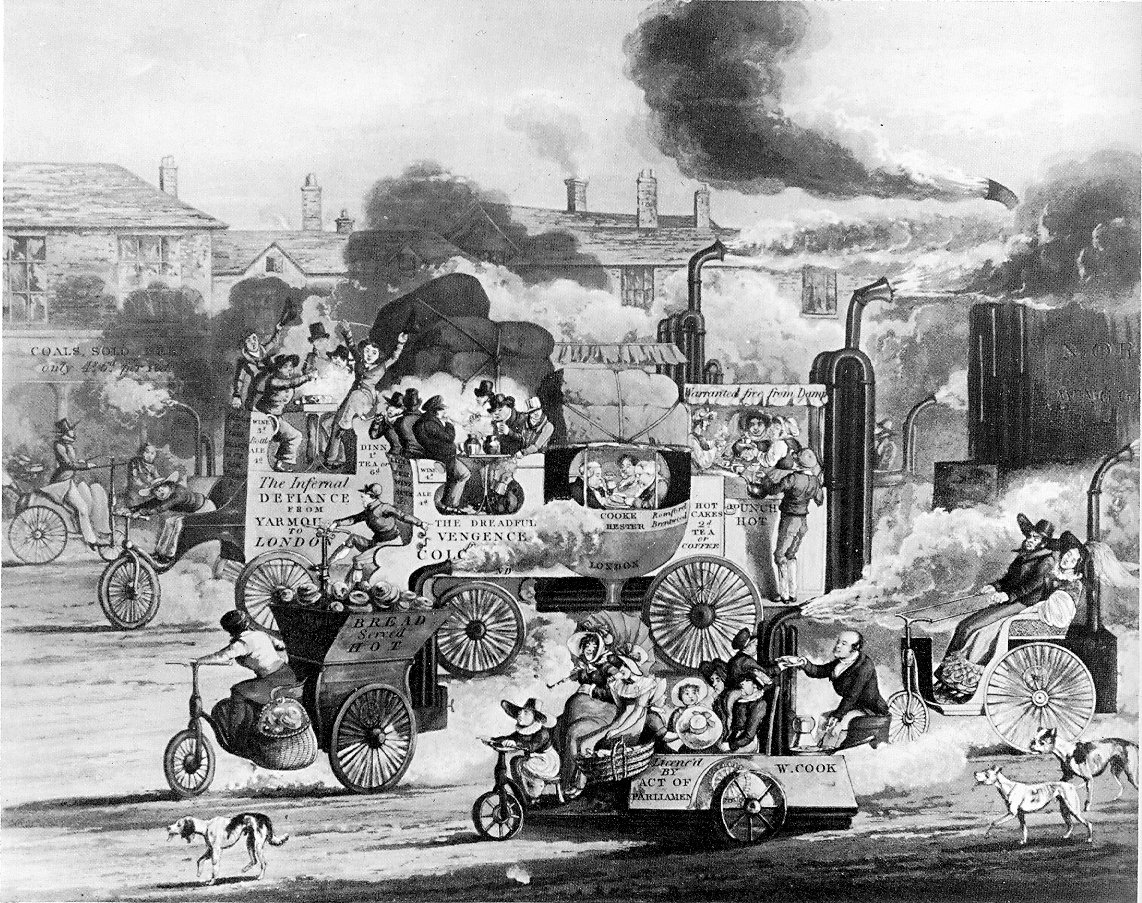

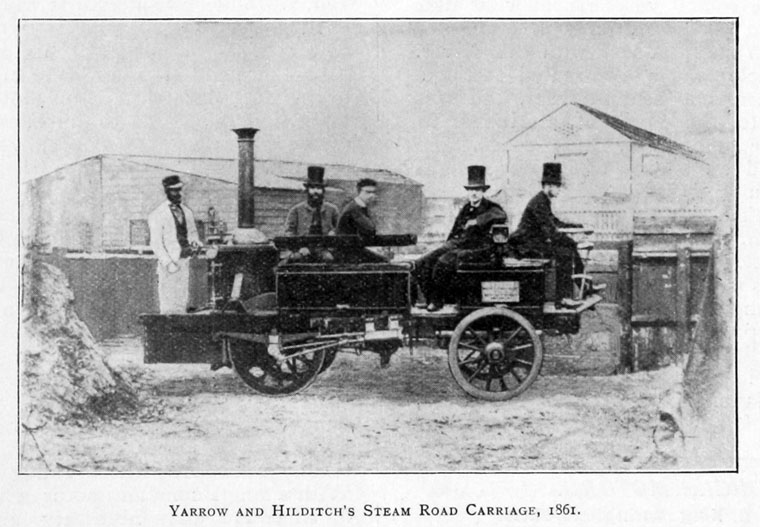

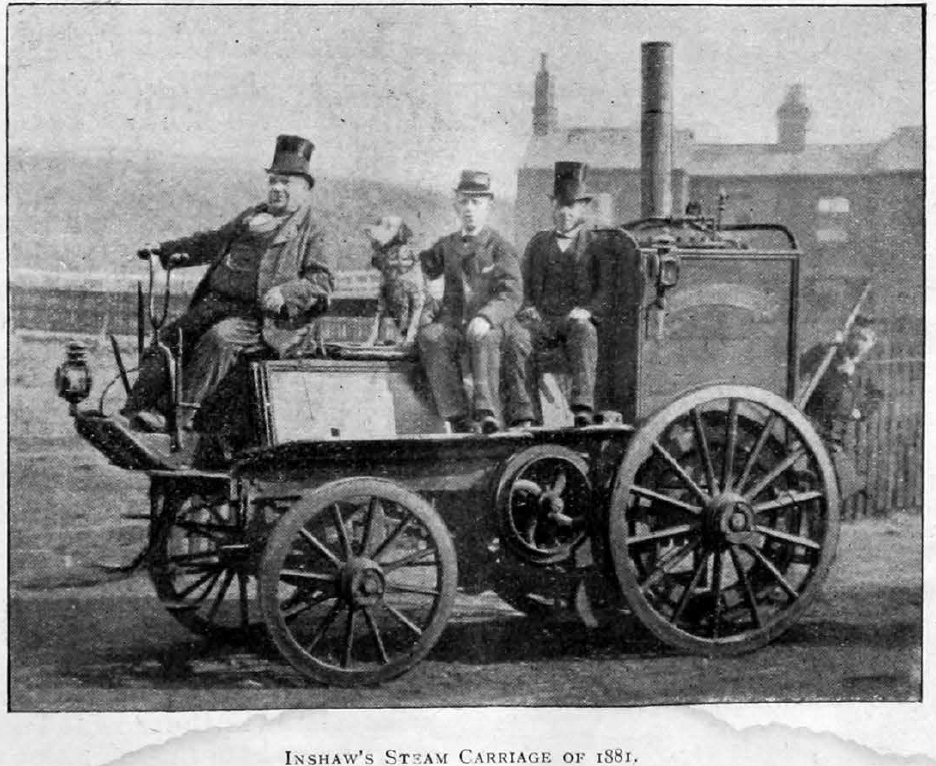

Yarrow and Hilditch, Hancock, Gurney, Dance, Summers and Ogle, Maceroni and Squire, Hills, Russell, Church, Redmund were the real pioneers of the motor movement.

Claude Johnson (“The early history of motoring”, 1927) wrote, “The extraordinary foresight and initiative of the men who designed those vehicles, were crushed by the criminal legislation introduced by the opponents to progress and those who feared that their financial interests would be endangered by the perfection of the mechanical road vehicle.

The law which drove the steam coaches of Hancock, Gurney and others off the British roads is largely responsible for the fact that the United Kingdom was for some time to the rear in the race for the supremacy of the motor industry.”

Anthony Bird (“The motor car 1765-1914”, 1960) wrote, “Before 1865 legislative restrictions upon motor-cars were not too severe the toll charges were relied upon to suppress them. Mechanical vehicles were allowed to travel at 10 m. p. h. in the country and 5 m. p. h. in towns and otherwise they were only subject to such control in the matters of "furious driving" or causing danger or nuisance as applied to ordinary traffic.

As the turnpike system gradually died away it was thought necessary to tighten the reins, and the Act of 1865 provided that each road locomotive should have in attendance upon it, whilst in motion, at least three persons one of whom should walk sixty yards ahead showing a red flag by day or a red lamp by night. Speed was limited to 4 m.p.h in the country and 2 m. p. h. in towns, but the Local Government Board was given power to impose further restrictions. (This was what became known as the Red Flag Act.)

The Act of 1878 was largely concerned with niggling technical details: width of tires, weight on axles, smoke consuming and so forth. The attendant to walk in front had now to precede the engine by only twenty yards and it was no longer specified that he should carry a flag. But wide powers were again left to the Local Government Board and the flag continued to be carried, and the public (and police) certainly acted as though it was still required.

In this atmosphere it is hardly surprising that only a few pioneers struggled against restriction; fortunately, even in times of stagnation, the English soil will always nourish the eccentric or the opponent of the status quo and the lamp of English inventiveness and resource, though dim, was kept burning.

The occasional steam-carriage continued to be made during the period 1850-80, but these did not make any contribution to the development of the motor-car with the exception of one built in 1868 by J. H. Knight. His road steamer, as he himself admitted, was not particularly satisfactory, but the experience gained with it must have been of use some twenty-five years later when Knight made one of the first petrol-driven vehicles to be built in this country. The first is believed to be the tricycle made between 1884 and 1887 by Edward Butler, but this machine, though containing many ingenious features, was not a practical success and the inventor, being unable to try it on the road adequately, gave up in despair.”

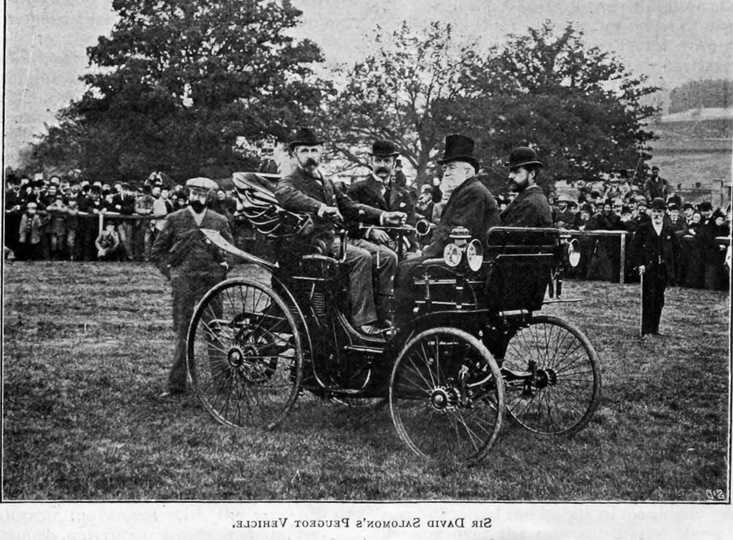

Claude Johnson (“The early history of motoring”, 1927) wrote, «By 1895 in the United Kingdom public opinion had so far recognized that automobiles had a future. Mr. Shaw-Lefevre, M. P., being the President of the Local Government Board, prepared a Light Locomotives Act, which was not proceeded with in consequence of the defeat of the Ministry, which led to a General Election. It provided that every county should create its own byelaws. The Paris-Bordeaux-Paris race of June, 1895, still further increased public interest in the future of the motor-car, and Sir David Salomons did his utmost to stimulate this interest.

Sir David Salomons (1851-1925)

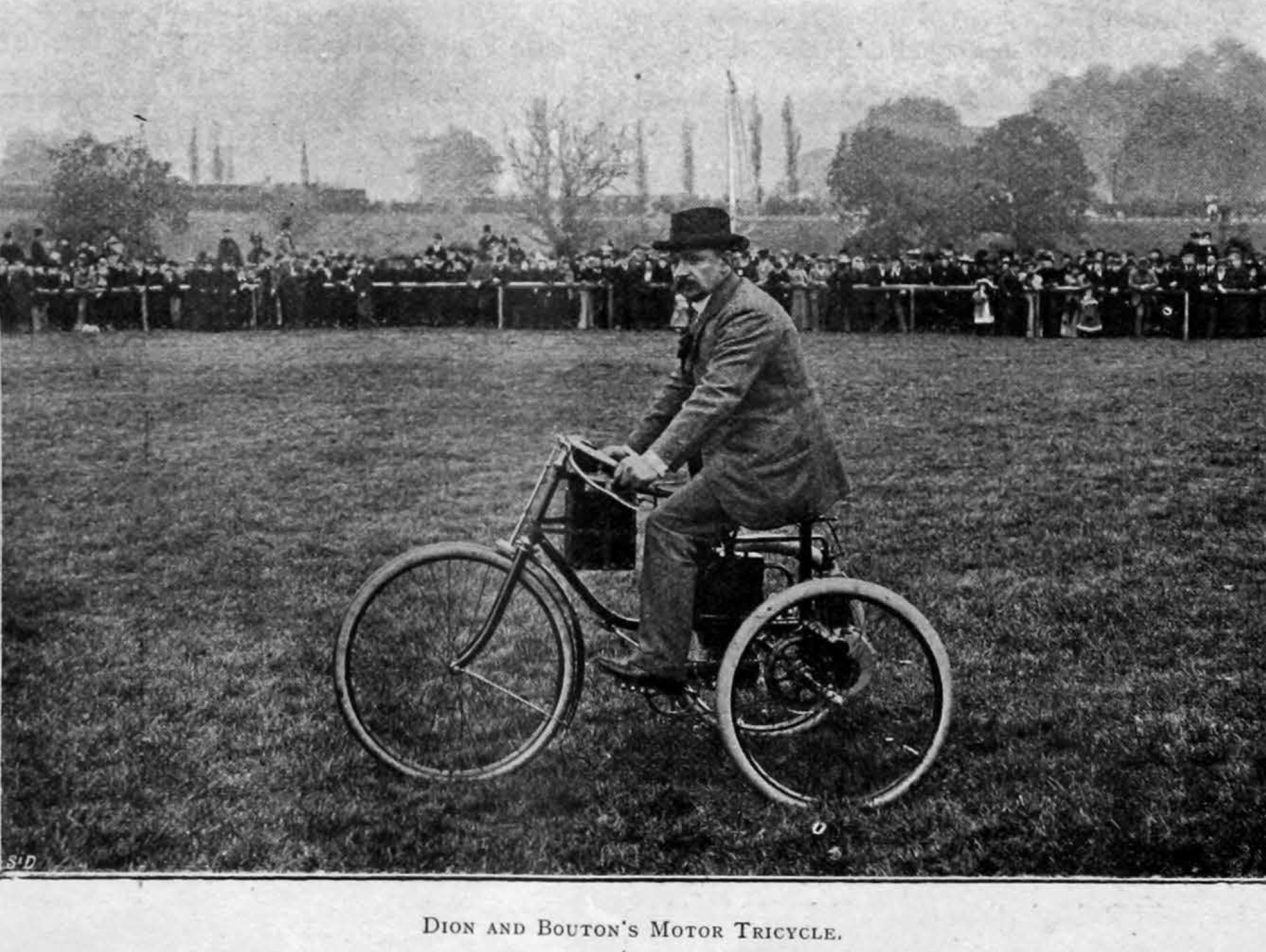

On Tuesday, October 15th, 1895, Sir David Salomons, who was then Mayor of Tunbridge Wells, held an exhibition of motor-vehicles in connection with the Tunbridge Wells Agricultural Show. The motor-vehicles were demonstrated on rough, soft grass before 5,000 spectators, the vehicles being: Sir David Salomons's 3 h. p. "Vis-a-vis" Peugeot, fitted with a Daimler engine made by Messrs. Panhard & Levassor; the Hon. Evelyn Ellis's Panhard & Levassor carriage; a De Dion Steam tractor attached to a landau, the front wheels of which had been removed; and a De Dion Bouton motor-tricycle with petrol engine and electric ignition.

It is notable, from the newspaper accounts of this exhibition, that the main objections taken to motor-vehicles on their first introduction to this country were: first, the vibration of the carriage when standing still; and, secondly, the smell of the petroleum spirit.

The fact that the cars would go up hill was considered to be highly satisfactory, for in No.1 of the Autocar one finds the following Statement: "Both Sir David Salomons' and the Hon. Evelyn Éllis's vehicles mounted the hill in the Show ground, which has a gradient of about in 40, in excellent form.

Following on Sir David Salomons's valuable educational exhibition, on October 28th, 1895 he wrote to the Daily Telegraph suggesting the formation of an association to deal with self-propelled locomotion, and asking that those who wished to join the association should write to him, and that the envelopes of such letters should be marked "Automobile."

The association was formed at a meeting convened by Sir David Salomons on Tuesday, December roth, 1895 at the Cannon Street Hotel. Between 300 and 400 people were present. Sir David Salomons urged that the immediate alteration of the law was necessary. Then came the deputation to Mr. Chaplin, with a view to bringing in a Bill, and throughout this period Sir David worked unceasingly, travelling to and from Paris and obtaining information from all parts of the world, so as to be well posted with information regarding the new movement. He also published various pamphlets and articles to show its advantages and to meet various arguments raised against it. In one of his pamphlets Sir David suggested the form of the Act of Parliament which, to all intents and purposes, was eventually adopted.

At the end of 1895 petitions were addressed to Mr. Henry Chaplin, then President of the Local Government Board, begging him to bring in a Bill to remove the restrictions on the use of automobiles, and Mr. Chaplin showed a hearty sympathy with the proposal.

At the end of 1895 the Engineer was also very enthusiastic concerning motor vehicles, and was organizing a trial, offering prizes of 1,000 guineas, and was collecting signatures for a memorial to the President of the Local Government Board regarding the use of motor vehicles on the roads.

Early in January, 1896, following the example of the Engineer, the Autocar inaugurated a petition to the House of Commons to pass a Bill which would allow light locomotives to run on the roads of the United Kingdom, and the cities of Birmingham, Coventry and Exeter were the first to sign independent petitions on the same lines.

In February, 1896, a deputation of the Self-Propelled Traffic Association, with Sir David Salomons as chairman, waited upon Mr. Henry Chaplin, the President of the Local Government Board, who was fully in sympathy with the object of the deputation, namely, the introduction of the Light Locomotives Bill.

In the following March Lord Harris introduced the measure into the House of Lords while the matter was under the consideration of a special Committee of the House of Commons.

At the end of April, Lord Harris secured the second reading of the Light Locomotives Bill in the House of Lords.

In March, 1896, a circular was issued by the Self-Propelled Traffic Association, in which mention of the following members was made: Sir David Salomons (President), Sir Frederick Bramwell, Mr. John Phillipson, Mr. Alfred Siemens (Vice-Presidents), and as members of Council, the Rt. Hon. Shaw Lefevre, Sir Albert K. Rollit, M.P., Professor Vernon Boys, F.R.S., Mr. W. Worby Beaumont, Mr. J. H. Knight, and Mr. Alfred Sennett, etc. In May the Self-Propelled Traffic Association memorialized the Chambers of Commerce with a view to getting the maximum weight of motor-vehicles as allowed in the new Bill increased to 4 tons.

On June 30th, 1896, Mr. Chaplin moved the second reading of the Light Locomotives Bill, and in the course of his speech he stated that if the Bill before the House became law during the then present Session, he believed it would undoubtedly develop a very great, and having regard to their experience in connection with bicycles, possibly an enormous trade, and give a vast amount of employment to the people of this country. He thought it was even possible that these motorcars might become a rival to light railways and that they were not at all unlikely to tend to decrease railway fares. He was convinced that they would be a great advantage and boon to the agricultural interest, in that they would enable the farmers to transport their produce at much less cost than they were able to do at present.

Mr. Martin, M. P., spoke in favor of the Bill, also Mr. Mundella, M. P. for Sheffield. He had seen motors in use in the South of France, which were a great success, and at least the question should have a fair trial.

In February, 1896, Mr. Frederick R. Simms announced the formation of the Motor-Car Club, and the arrangements made for a Motor Exhibition to be held at the Imperial Institute in the summer of that year; and the same month the Motor-Car Club gave a demonstration of motor-vehicles at the Imperial Institute, when the then Prince of Wales (afterwards His Majesty King Edward VII) was driven in the galleries and gardens of the Imperial Institute by Mr. Evelyn Ellis. On the next day a large number of Members of the House of Lords and House of Commons were present at a similar demonstration.

In October, 1896, Mr. Stanley Spooner founded the Automotor Journal, and from the outset resolved that his paper should be a fearless organ carried on for the and full information of the public, without reference to the likes or dislikes of his advertisers.”

Anthony Bird (“The motor car 1765-1914”, 1960) wrote, “Sir David Salomons' little display at Tunbridge Wells in October 1895, and H. J. Lawson's more ambitious affair at the Imperial Institute lent support to the efforts being made by Evelyn Ellis, Sir John Macdonald and other worthies to persuade the Government into removing the prohibition (for such it was) on motoring in England. The terms of a Bill were tentatively agreed between the Home Secretary Mr. Shaw Lefevre, the Self Propelled Traffic Association and the Local Government Board in the autumn of 1895 but the Government collapsed before this Bill was debated and it fell to the succeeding Home Secretary, Mr. Henry Chaplin, to present the Bill in the following Spring.

Opposition was considerable and followed much the same lines as that which had been arrayed against the first Railway Bills eighty years earlier: the spirit of Sibthorp1 still lived. The House of Lords, as it so often does, displayed a more reasoned attitude than the Commons and the Locomotives on Highways Act duly received the Royal Assent and became effective on the 14th November 1896.

The principal provisions of the act were that "locomotives" of less than 3 tons unladen weight were to be regarded as "light" and were exempted from the need for an attendant to walk in front (whether with or without flag is immaterial). A maximum speed of 14 m. p. h. was to be allowed, but power was given to the Local Government Board (which body is now, happily, no more) to reduce the permitted maximum and, typically, the Board promptly reduced the maximum to 12 m. p. h. Preparations were made by Lawson and his associates to celebrate the effective date of the Act by staging a triumphal procession of horseless carriages from London to Brighton.